12 years, 10 months ago by Karin Wiecha

13 years, 1 month ago by Kelsey Westphal

13 years, 3 months ago by Susan Colowick

13 years, 3 months ago by Richard Makin

13 years, 5 months ago by Laura Welcher

13 years, 6 months ago by Laura Welcher

13 years, 7 months ago by Laura Welcher

13 years, 8 months ago by Austin Brown

13 years, 9 months ago by Andréa Davis

14 years ago by Laura Welcher

14 years ago by Laura Welcher

PanLex, the newest project under the umbrella of The Long Now Foundation, has an ambitious plan: to create a database of all the words of all of the world's languages. The plan is not merely to collect and store them, but to link them together so that any word in any language can be translated into a word with the same sense in any other language. Think of it as a multilingual translating dictionary on steroids.

You may wonder how this is different from some of the other popular translation tools out there. The more ambitious tools, such as Babelfish and Google Translate, try to translate sentences, while the more modest tools, such as Global Glossary, Glosbe, and Logos, limit their scope to individual words. PanLex belongs to the second, words-only, group, but is far more inclusive. While Google Translate covers 64 languages and Logos almost 200 languages, PanLex is edging close to 7,000 languages. With the knowledge stored in PanLex, translations can be produced extending beyond those found in any dictionary.

Here’s an example to give the basic idea of how it works. Say you want to translate the Swahili word ‘nyumba’ (house) into Kyrgyz (a Central Asian language with about 3 million speakers). You’re unlikely to find a Swahili–Kyrgyz dictionary; if you look up ‘nyumba’ in PanLex you’ll find that even among its half a billion direct (attested) translations there isn’t any from this Swahili word into Kyrgyz. So you ask PanLex for indirect translations. PanLex reveals translations of ‘nyumba’ that, in turn, have four different Kyrgyz translations. Three of these (‘башкы уяча’, ‘үй барак’, and ‘байт’) each have only one or two links to ‘nyumba’. But a fourth Kyrgyz word, ‘үй’, is linked to ‘nyumba’ by 45 different intermediary translations. You look them over and conclude that ‘үй’ is the most credible answer.

How confident can you be of your inferred translation—that Swahili ‘nyumba’ can be translated into Kyrgyz ‘үй’? After all, anyone who has played the game of “translation telephone” (where you start with Language A, translate into Language B, go from there to Language C and then translate back to Language A) will know this kind of circular translation can result in hilarious mismatches. But PanLex is designed to overcome “semantic drift” by allowing multiple intermediary languages. Paths from ‘nyumba’ to ‘үй’, for example, run through diverse languages from Azerbaijani to Vietnamese. Based on such multiple translation paths, translation engines can provide ranked “best fit” translations. As the database grows, especially in its coverage of “long tail” languages, possible translation paths will multiply, boosting reliability.

There are a couple of demonstrations that you can try with a browser. This will give you a sense of the magnitude of the data and the potential power of the database as a tool. One of these is TeraDict. If you enter a common English word like ‘house’ or ‘love’ you are likely to get translations into hundreds, or even thousands, of languages, and in some cases many translations per language. French, for example, has 25 translations for ‘house’ and 55 translations of ‘love’, including ‘zéro’ (hint: Think tennis!). Two similar interfaces allow you to explore the database in either Esperanto—InterVorto—or Turkish—TümSöz.

The second web tool, PanLem, is considerably more complicated and is used mostly by PanLex developers to enlarge and evaluate the database. But it’s publicly accessible. There is a step-by-step "cheat sheet" to help you climb the learning curve.

PanLex is an ongoing research project, with most of its growth yet to come, but the database already documents 17 million expressions and 500 million direct translations, from which billions of additional translations can be inferred.

PanLex is being built using data from about 3,600 bilingual and multilingual dictionaries, most in electronic form. The process of ingesting data into the database involves substantial curation and standardization by PanLex editors to ensure data quality. The next stage of collection will likely involve dictionaries that exist only in print form. It is hard to say how many are out there, but we expect it is on the order of tens of thousands. It is likely that most of these have not been scanned or digitized. Once they are, there will be a significant effort to improve the optical character recognition (OCR) for these materials—an effort which is likely to be highly informative to the development of OCR technology, since it will involve the human identification of many forms of many different scripts for languages around the world.

PanLex is working closely with the Rosetta Project. PanLex is a wonderful realization of the Rosetta Project’s original goal in building a massive, and massively parallel, lexical collection for all of the world’s languages.

14 years, 5 months ago by Austin Brown

14 years, 6 months ago by Laura Welcher

14 years, 7 months ago by

14 years, 8 months ago by Laura Welcher

Did you know...

There is something you can do to help document and promote the languages used in your own community! We need your help to meet our goal of recording 50 languages in a single day! How many languages can you help us document? Bring yourself and your multilingual friends and be the stars of your own grassroots language documentation project!

Professional linguists and videographers will be on site to document you and your friends speaking word lists, reading texts, and telling stories. You can also document your language using tools you probably have in your purse or back pocket — a mobile phone, digital camera, or laptop — just bring your device and our team will guide you through the documentation process.

How do your words and stories make a difference? An important part of language documentation is building a corpus — creating collections of vocabulary words, as well as conversations and stories that demonstrate language in use. From a corpus, linguists and speech technologists can build grammars, dictionaries, and tools that enable a language to be used online. The bigger the corpus, the better the tools!

The recordings you make during the event will be added to The Rosetta Project's open collection of all human language in The Internet Archive. And, you can compete for cool prizes, including an iPad 2 for the participant who records and uploads the most languages during the event!

Please

We will be in touch soon with more information about the day's events, and how you can participate! For questions or more information please contact rosetta@longnow.org.

14 years, 9 months ago by Harry Willoughby

14 years, 10 months ago by Alex Mensing

15 years ago by Austin Brown

15 years, 1 month ago by Laura Welcher

On January 9, The Rosetta Project presented a poster at the Linguistic Society of America annual meeting, describing a distributed archive model we've developed and implemented with the Rosetta digital collection. Here is a video describing this model, and some of its long-term benefits:

A pdf of this poster is available for download here (12 MB).

15 years, 2 months ago by Austin Brown

15 years, 4 months ago by Laura Welcher

Save the Words is a nifty site by the Oxford English Dictionary where lexophiles can adopt an esoteric or obsolete word and revive its use. And get the t-shirt. It would be a fun educational tool in the context of an endangered language, where all of the words need saving.

15 years, 7 months ago by Adrienne Mamin

Egyptian Hieroglyphs on The Rosetta Stone were deciphered by scholars, but a new computer program written at MIT could potentially accomplish the same feat today:

“'Traditionally, decipherment has been viewed as a sort of scholarly detective game, and computers weren't thought to be of much use,’ study co-author and MIT computer science professor Regina Barzilay said in an email.” (quoted in this recent writeup in the National Geographic Daily News).

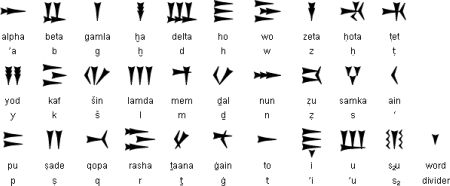

The language in this case is Ugaritic, written in cuneiform and last used in Syria more than three thousand years ago. Archaeologists discovered Ugaritic texts in 1928, but linguists didn’t finish deciphering them for another four years. The new computer program did it in a couple of hours.

While an exciting and significant first step, the program is not a silver bullet solution to language decipherment. Human beings figured out Ugaritic long before the computer program came along, and it remains to be seen how well the program works with a never-before-deciphered language. Furthermore, the program relied on comparisons between Ugaritic and a known and closely related language, Hebrew. There are some languages with no known close relatives, and in those cases, the computer program would be at a loss.

Of course, we can’t be certain exactly how the technology may progress in the future. But with the Rosetta Disk designed to last for thousands of years, and with hundreds of languages classified in the Ethnologue as nearly extinct, an automated decoder of language documentation seems likely to prove useful eventually. It’s nice to know we’ve made a promising start.

15 years, 7 months ago by Laine Stranahan

The Rosetta Project is pleased to announce the Parallel Speech Corpus Project, a year-long volunteer-based effort to collect parallel recordings in languages representing at least 95% of the world's speakers. The resulting corpus will include audio recordings in hundreds of languages of the same set of texts, each accompanied by a transcription. This will provide a platform for creating new educational and preservation-oriented tools as well as technologies that may one day allow artificial systems to comprehend, translate, and generate them.

Huge text and speech corpora of varying degrees of structure already exist for many of the most widely spoken languages in the world---English is probably the most extensively documented, followed by other majority languages like Russian, Spanish, and Portuguese. Given some degree of access to these corpora (though many are not publicly accessible), research, education and preservation efforts in the ten languages which represent 50% of the world's speakers (Mandarin, Spanish, English, Hindi, Urdu, Arabic, Bengali, Portuguese, Russian and Japanese) can be relatively well-resourced.

But what about the other half of the world? The next 290 most widely spoken languages account for another 45% of the population, and the remaining 6,500 or so are spoken by only 5%--this latter group representing the "long tail" of human languages:

Equal documentation of all the world's languages is an enormous challenge, especially in light of the tremendous quantity and diversity represented by the long tail. The Parallel Speech Corpus Project will take a first step toward universal documentation of all human languages, with the goal of providing documentation of the top 300 and providing a model that can then be extended out to the long tail. Eventually, researchers, educators and engineers alike should have access to every living human language, creating new opportunities for expanding knowledge and technology alike and helping to preserve our threatened diversity.

This project is made possible through the support and sponsorship of speech technology expert James Baker and will be developed in partnership with his ALLOW initiative. We will be putting out a call for volunteers soon. In the meantime, please contact rosetta@longnow.org with questions or suggestions.

18 years, 11 months ago by Alexander Rose

On January 2nd of 02007 Stewart Brand and I stepped into the cool deep past and unknown future of who begat who.

The Granite Genealogical Vaults

Since I began working on the 10,000 Year Clock project, and associated Library projects here at Long Now almost a decade ago, I have heard cryptic references to this archive. We have visited the nuclear waste repositories, historical sites, and many other long term structures to look for inspiration. However we had never found a way to see this facility. This is the underground bunker where the Mormons keep their genealogical backup data, deep in the solid granite cliffs of Little Cottonwood Canyon, outside Salt Lake City. UT.

The Church has been collecting genealogical data from all the sources it can get its hands on, from all over the world, for over 100 years. They have become the largest such repository, and the data itself is open to anyone who uses their website, or comes to their buildings in downtown Salt Lake City.

However they dont do public tours of the Granite Vaults where all the original microfilm is kept for security and preservation reasons. Since Stewart had recently given a talk at Brigam Young University we were able to request access, and the Church graciously took us out to lunch and gave us a tour.

19 years ago by Alexander Rose